Sanger Sequencing and Early Genome Research

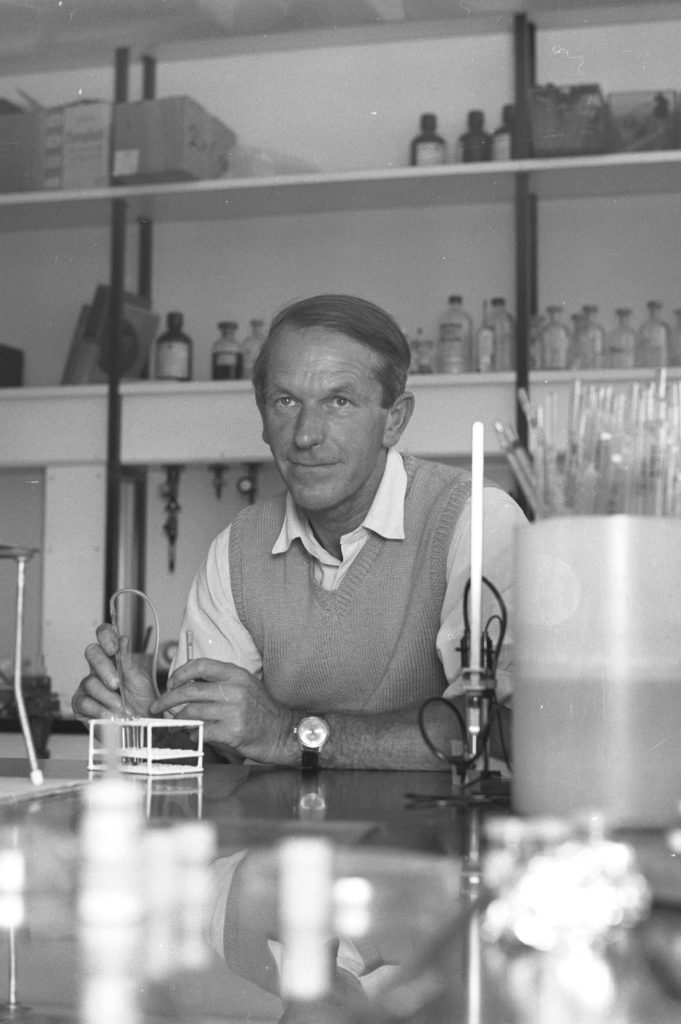

Photograph | Letter by Letter

Despite much effort to understand the structure of the DNA molecule, working out a method to read (known as sequencing) the order of its four chemical bases (shown as letters: A, C, G and T) posed a greater challenge. As Fred Sanger noted, part of the problem was the size of genomes – even those of small organisms like bacteria, have thousands of letters.

It is not possible to sequence a genome from one end to the other, it needs to be broken into fragments, sequenced, and then the information reassembled. In DNA sequencing nature’s own way of copying DNA is adapted so that when a DNA base, labelled with radioactivity (and later, colour), is inserted it stops the process. This method results in lots of pieces of labelled DNA of different lengths that can then be read by the sequencing machine.

Sanger Sequencing was refined and scaled up in the 1980s so that it could be applied to reading the genomes of more complex organisms like worms, flies, and eventually humans. Although the technique and its efficiency was much improved by moving from lab bench tanks to powerful machines, gel sequencing remained the only sequencing technology until the late 1990s.