Reflections by Chrystal Ding

Photographer Chrystal Ding's reflections on counselling as a human experience.

From 2017-2019 I spoke to 23 people for Genetopia, a book of photographs, interviews, and personal documents through which these individuals told the stories of their journeys with DNA testing – why they did it, what they found, and what they did with that information.

Of the 23 people I interviewed, only those who had been referred to a genetic counsellor by a doctor had ever heard of one. For others, any information raised by their DNA test results was theirs to Google, information that included newfound family relations and hereditary conditions. The individuals were often surprised to learn that there are people in the world trained to provide exactly the support and answers that they might have been looking for. More than a few wished they had known earlier.

In my documentary photography practice I often focus on issues of trauma and identity. In 2019 I have been working on a project funded by the Rebecca Vassie Memorial Trust, which looks at counselling in a very different context: that of genocide survivors in rural Rwanda.Though the two projects might seem worlds apart, one thing that is emerging as a common thread is how indelibly linked trauma, identity, and healing are. And genetics occupies the particularly complex space between the science of who we are and our lived experience of the world. How we absorb and take on information relating to our identity dictates our experience of it, and often sends us off in one direction or another.

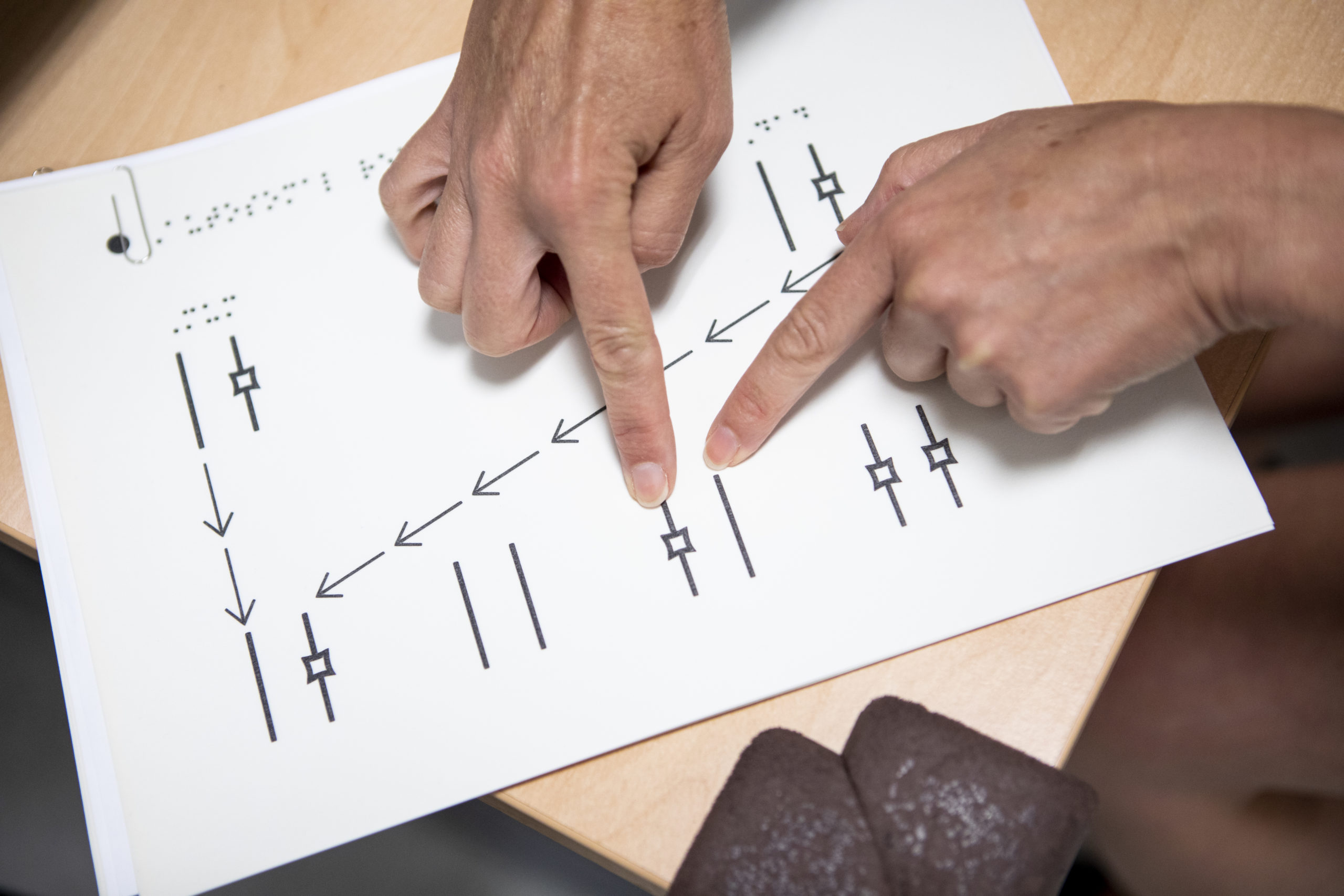

Before I visited Rwanda I couldn’t even imagine what counselling would look like there. Where would it take place? Who would be involved? What does ‘counselling’ mean and do in that situation? Similar questions came to mind when I thought about genetic counselling. Empowering People was a way of accessing those spaces and the people who work in them to get a better understanding of what it is they do, and why it is important.

At its core, genetic counselling – like any form of counselling – is a very human-centric experience, and it was in the details that this came through for me. In Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, genetic counsellor Amy Goldman explained to me how she used to place the tissue box on the edge of the table to be easy to reach, but over time realised that it could lead patients to expect bad news where there wasn’t any, and subsequently the box was placed further out of sight. In St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester, there are special provisions for ophthalmic genetic counselling where patients might be visually impaired. In many of the clinic rooms chairs are arranged with arms touching, mimicking where their occupants hold hands. And where there are children, the bright shock of toys that translates any clinical setting into a room for family.

At the heart of any counselling relationship is the connection between the counsellor and the person or persons in their care. In many ways similar to photography, attention is key – attention to detail, attention to the individual, and to the space in which the relationship is forged. The photographs taken for this exhibition are an attempt to show some of these aspects of the care involved in the handling and navigating of our genetic information by genetic counsellors.

Chrystal Ding

Documentary Photographer / Writer

www.chrystalding.com